‘System positive’ is our shorthand for companies that we believe will thrive in the transition to sustainability. Such companies are also helping to enable and drive the changes we need to see in economic and social systems.

As we explored in a previous Insights piece, today’s ESG data has important limitations. It focuses on the how not the what. By ‘how’, we mean that companies conduct their business in a long-term, responsible way, with regard to all stakeholders. By ‘what’, we mean that companies produce goods and services aligned with the society we want.

It is also anchored to past performance rather than forward-looking. Yet, we know that many sectors need to undergo a profound transition in the coming years to achieve sustainability. A waste management firm might be doing well on recycling rates, but how will it fare if consumers and policymakers get serious about a zero waste, circular economy? A food producer might be improving its environmental footprint, but is it ready for a switch to healthier diets?

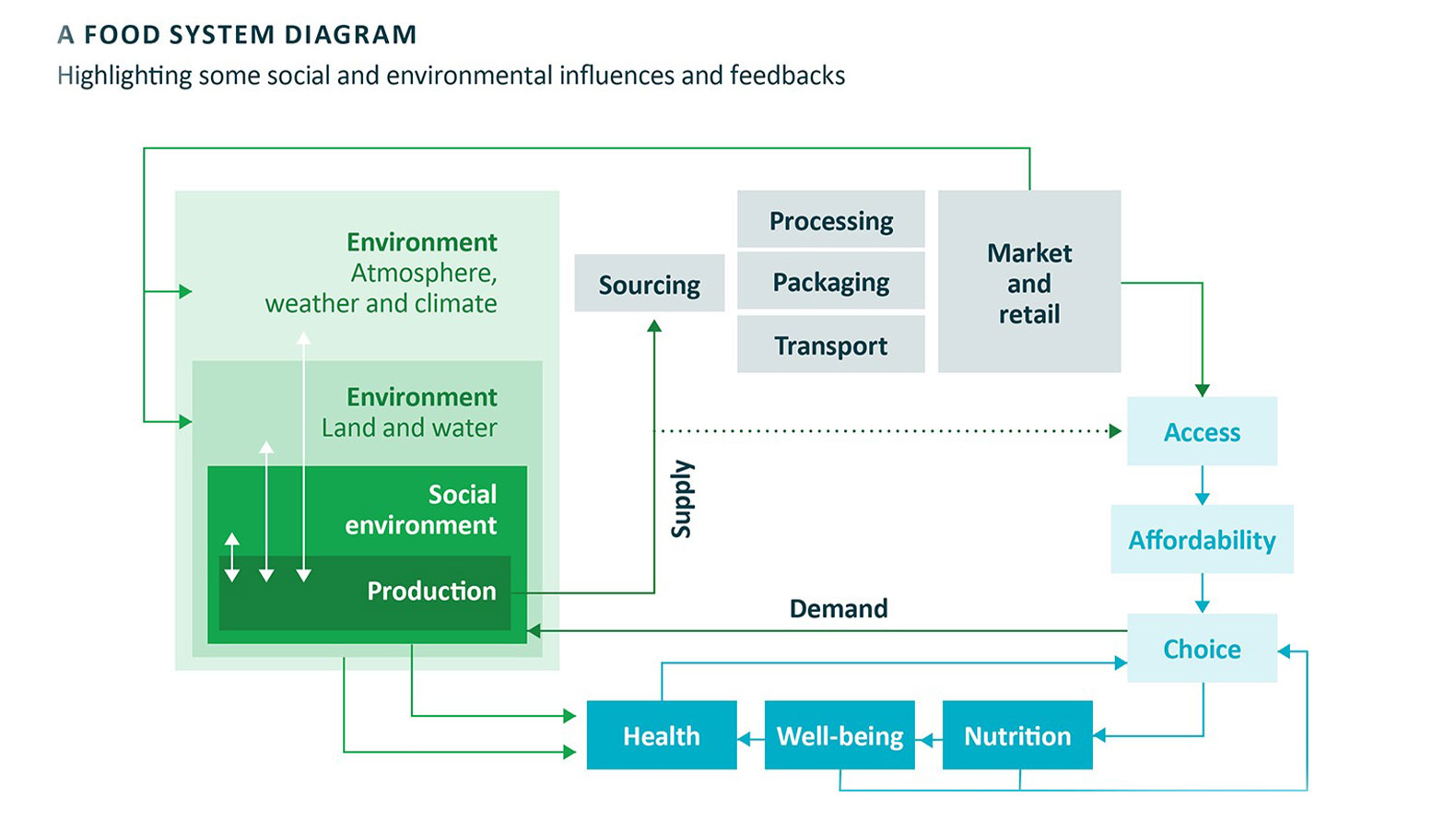

As 2020 has surely demonstrated, if you ignore systemic risks, you can miss what really matters. Yet, applying systems thinking to investing is easier said than done. Reports on sustainability are often filled with complicated diagrams illustrating many feedback loops. Even small changes in such systems can lead to tipping points and cascades of impact. There are few straightforward calculations here to be plugged into a discounted cash flow analysis.

To bridge this gap, our analysts spend much of their time exploring the wider industrial, social and ecological context in which companies operate. We look at the changes required according to major scientific assessments and consider the impact on the company. We also look at whether we think the company can and will be a catalyst to bring such a future about.

For some companies, we find it quite straightforward to determine that the company is system positive. The suppliers of equipment for electrified vehicles should benefit from the shift to electrified mobility and renewable energy. In contrast, a company producing a more efficient internal combustion engine is providing some short-term positive benefit, but stands to lose as the transition to zero carbon mobility accelerates.

For many companies, however, the answer is less obvious. Most companies form only one part of an industrial ecosystem that needs to transform to address our environmental and social crises. The company may be well positioned under a strong vision for sustainability, but at the same time benefit from the status quo. Plus, emerging knowledge on systems and sustainability often leads us to revisit our thinking on particular companies.

In the next section we take a brief look at the key questions we ask ourselves to determine that a company is system positive. For the rest of this piece, we explore this through the example of food systems.